A practical guide to Clean Architecture, with a personal touch.

Just last Sunday, I was randomly browsing GitHub, (like most of my Sundays usually go) and I stumbled upon a very popular repository, with over 10K commits. Now I am not going to name which project it was but it should suffice to say that even though I knew the stack of the project, the code itself was completely alien to me. Some features were randomly thrown adrift a sea of loosely cohesive functions inside directories called “utils” or worse, “helpers”.

The catch with big projects is that overtime, they become so complex that it is actually cheaper to re-write them rather than training new talent to actually understand the code and then contribute.

This brings me to the ulterior motive of the rather practical anecdote, which is to talk about Clean Architecture, at an implementation level. Now this blog is going to contain some Go code, but fret not, even if you are not familiar with the beautiful language, the concepts are fairly easy to grok.

What is so Clean about Clean Architecture?

In short, you get the following benefits from using Clean Architecture:

- Database Agnostic : Your core business logic does not care if you are using Postgres, MongoDB, or Neo4J for that matter.

- Client Interface Agnostic: The core business logic does not care if you are using a CLI, a REST API, or even gRPC.

- Framework Agnostic: Using vanilla nodeJS, express, fastify? Your core business logic does not care about that either.

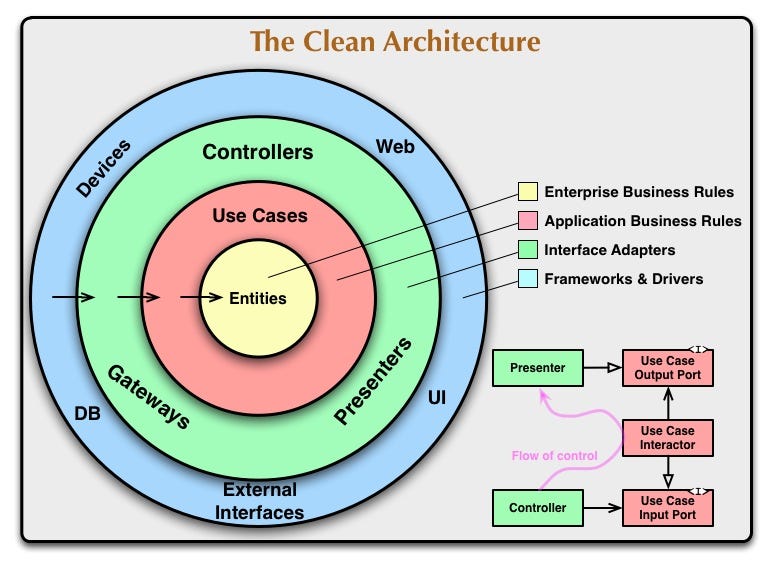

Now if you want to read more about how clean architecture works, you can read the fantastic blog, The Clean Architecture, by Uncle Bob. For now, lets jump to the implementation. To follow along, view the repository here.

Clean-Architecture-Sample

├── api

│ ├── handler

│ │ ├── admin.go

│ │ └── user.go

│ ├── main.go

│ ├── middleware

│ │ ├── auth.go

│ │ └── cors.go

│ └── views

│ └── errors.go

├── bin

│ └── main

├── config.json

├── docker-compose.yml

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

├── Makefile

├── pkg

│ ├── admin

│ │ ├── entity.go

│ │ ├── postgres.go

│ │ ├── repository.go

│ │ └── service.go

│ ├── errors.go

│ └── user

│ ├── entity.go

│ ├── postgres.go

│ ├── repository.go

│ └── service.go

├── README.md

Entities

Entities are the core business objects that can be realized by functions. In MVC terms, they are the model layer of the clean architecture. All entities and services are enclosed in a directory called pkg. This is actually what we want to abstract away from the rest of the application.

If you take a look at entity.go for user, it looks like this:

{% gist https://gist.github.com/L04DB4L4NC3R/04efd6e4659f7aab367523e52b0aa839 %}

Entities are used in the Repository _i_nterface, which can be implemented for any database. In this case we have implemented it for Postgre, in postgres.go. Since repositories can be realized for any database, therefore they are independent of all of their implementation details.

{% gist https://gist.github.com/L04DB4L4NC3R/0f6862642ff871b1a754af9829c2ac18 %}

Services

Services include interfaces for higher level business logic oriented functions. For example, FindByID, might be a repository function, but login or signup are service functions. Services are a layer of abstraction over repositories by the fact that they do not interact with the database, rather they interact with the repository interface.

{% gist https://gist.github.com/L04DB4L4NC3R/9a457875a046e438fd0a76115db272f7 %}

Services are implemented at the user interface level.

Interface Adapters

Each user interface has it’s separate directory. In our case, since we have an API as an interface, we have a directory called api.

Now since each user-interface listens to requests differently, interface adapters have their own main.go files, which are tasked with the following:

- Creating Repositories

- Wrapping Repositories inside Services

- Wrap Services inside Handlers

Here, Handlers are simply user-interface level implementation of the Request-Response model. Each service has its own Handler. See user.go

{% gist https://gist.github.com/L04DB4L4NC3R/1b85ee1ac967163139465dda80a0f3b5 %}

Error Handling

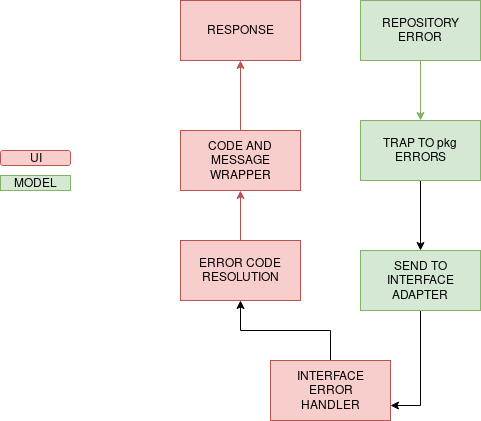

The basic principle behind error handling in Clean Architecture is the following:

Repository errors should be uniform and should be wrapped and implemented differently for each interface adapter.

What this essentially means is that all of the database level errors should be handled by the user interfaces differently. For example, if the user interface in question is a REST API then errors should be manifested in the form of HTTP status codes, in this case, code 500. Whereas if it is a CLI then it should exit with status code 1.

In Clean Architecture, Repository errors can be at the root of pkg so that Repository functions is able to call them in case of a control flow miscarriage, as seen below:

{% gist https://gist.github.com/L04DB4L4NC3R/42c6d8fdc9885666707e1cc680b213f0 %}

The same errors can then be implemented according to the specific user interface, and can most often be wrapped in views, at the Handler level, as seen below:

{% gist https://gist.github.com/L04DB4L4NC3R/c407b1530a0ca915372cd0ba4652dec8 %}

Each Repository level error, or otherwise, is wrapped inside a map, which returns an HTTP status code corresponding to the appropriate error.

Conclusion

Clean Architecture is a great way to structure your code and then forget about all of the complexities that might arise due to agile iterations or rapid prototyping. Being database, user interface, as well as framework independent, Clean Architecture clearly takes the cake for living up to its name.

References

This Article was originally published on Medium under Developer Student Clubs VIT, Powered By Google Developers. Follow us on Medium.